2018 has begun on a high note for India— with top diplomatic meets organized with key Eurasian State-Leaders. Be it Indian Prime Minister visiting West Asia or Iran signing a dozen MoUs with India or Jordan’s King Abdullah exploring India-Jordan relations in a three-day visit. All, in recent times, highlight India’s active persuasion of Eurasian nations— Russia, Central Asia and West Asia to be more specific. Given the abundance of hydrocarbons and their strategic location on the world map, it is natural for India, an emerging global power— albeit with scanty energy resources, to seek bilateral ties in the region. However, this partnership is not limited to energy or connectivity issues alone— it has more deep rooted concerns, such as countering terrorism and China’s expansionist policy.

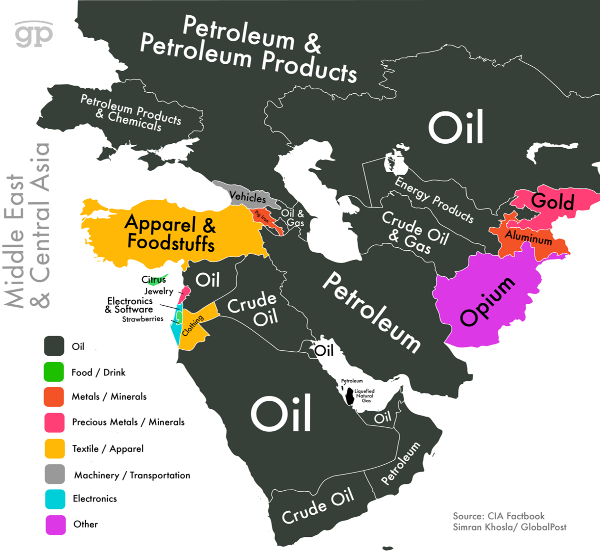

Often, past or present, Eurasia has served as the geopolitical landscape for foreign policy mitigation; having gradually become the seat of consular arm twisting for the powerful, and on the other a potential resource center of the energy starved nations (especially India and China). Some of the world’s largest oil & gas suppliers— Central Asia, Middle-East and Russia— are located here; and given the phenomenal economic growth of the surrounding developing nations, the Eurasian influence is undeniable. No doubt, then, Halford John Mackinder, in 1904, suggested central Eurasia as the ultimate continental power along with Africa. In his article “The Geographical Pivot of History”, Mackinder described this “heartland” as the greatest natural fortress surrounded on all sides by ecological barriers.

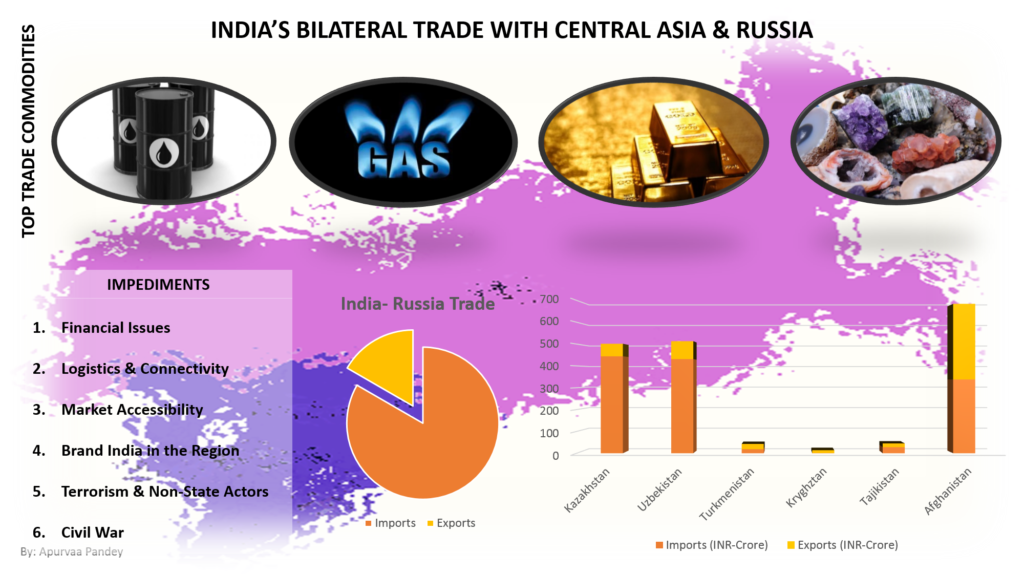

Geography, then, certainly is significant to the foreign policy of States. Acknowledging which, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2015 visited Russia and the five Central Asian States— Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan subsequently; closely followed by his State visits to key Middle East nations. The prominent bottlenecks in India- Eurasia relationship as such are:

- Connectivity— the Central Asia states, in particular Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, are landlocked oil & gas rich nations. For India to partake in trade with the Caspian region, India needs to establish enhanced connectivity modes. Apart from INSTC, a rigorous pipeline diplomacy is the need of the hour.

- Terrorism and Non-State Actors— Non-state outfits like Taliban and IS have plagued the region, creating hindrances in commercial flow from the Central Asian states as well. West Asia is inflicted by civil war and constant terrorist infiltration, which functions as a destabilizing factor especially for fragile states like those of Afghanistan.

Therefore, over the years, the strategic themes of Modi’s visit to these nations has been increased connectivity, energy trade, and countering terrorism; apart from shared cultural and historical linkages of the regions. This clearly indicates a re-orientation of India’s foreign policy with a renewed interest in Central Asia. This new wave has factored in:

- Multipolar World— Shift in balance-of-power, i.e. with the US no longer sole superpower;

- Rise of anti-state organizations, especially in Middle-East, who are ready to block land route to Central Asia;

- Increased Chinese intervention in the region and

- Reinforcement of revisionist states and identity politics versus globalization.

Of note, the years following the disintegration of USSR saw an attempt of Russia and China to establish joint-influence over the region. In this light, India’s relatively soft approach is much welcomed by the Central Asian States.

All this definitely has a role in the larger scheme of things— wherein India’s future energy security and sovereignty are protected. One look at the energy commodities map of the Central Asian and Middle- Eastern States will enable one to understand and praise the adeptness of Indian government for the prompt strategic planning, in light of changing geopolitical landscape.

India, prior to Connect Central Asia approach, did not have any specific policy towards Central Asia as such. Given the ominous presence of China in the region, India needs to affix its road to development looping in the Central Asian states; or it will stand at the risk of losing out due to lack of vision and action, as it did in case of Kashmir, Tibet and Myanmar among others. However, having recognized this as the opportune time to establish a direct connect with the energy basin of the world, India has successfully taken some decisive steps in the direction. These include accession to Shanghai Cooperative Organization, Ashgabat Agreement, Pipeline diplomacy (including TAPI and IPI), International North South Transport Corridor and the on-going India and Eurasian Economic Union Trade Pact. The common thread here being— enhanced connectivity between Caspian Sea, Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

- International North South Transport Corridor

One of the earliest in the series is the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC), inked in September 2000. INSTC, a 7200 Km long land and sea based multi-modal transport system, is expected to catalyze bilateral trade and commerce amongst the countries —Russia, Iran and India. In these last few years, eleven countries have joined the project— namely Azerbaijan, Armenia, Bulgaria (observer status), Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Oman, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey and Ukraine. In fact in September 2017, India and Turkmenistan discussed the possibility of linking INSTC to Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan- Iran rail link.

“A study by the Federation of Freight Forwarders’ Associations in India showed that INSTC would be 30% cheaper and 40% shorter than existing routes. A shipment on the dedicated transport corridor would take an average of 23 days, with freight costs of around USD 2,300 to USD 3,500 for a dry container and USD 4,600 to USD 6,800 for a reefer container. This is extremely swift in comparison to the 45-60 days it takes for the goods to reach Europe through the Suez Canal. As per the first freight test run… in 2016, movement from Mumbai to St. Petersburg via INSTC took only three weeks as compared to the six weeks it would require via the sea.”

- Shanghai Cooperative Organization

Next, India acceded to the Shanghai Cooperative Organization (SCO), during the 2017 Astana Summit, which has allowed it to avail excellent geo-strategic and economic opportunities. Given, India is an energy hungry nation, SCO will enable the country to exercise regional diplomacy and push for the otherwise pending energy projects. These include IPI (Iran-Pakistan-India) pipeline, TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) pipeline, and CASA (Central Asia-South Asia)-1000 electricity transmission projects. Additionally, the SCO FTA, due in 2020, will further help India to enhance its low trade dealings, currently at $500 million, with Central Asian States.

- Ashgabat Agreement

India’s accession to Ashgabat Agreement is another significant step towards establishing better trade connectivity of India with Central Asia and Persian Gulf. Briefly, Ashgabat Agreement aims at creating an International Transport and Transit Corridor between Iran, Oman, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan; which will enable India to enhance its commercial interface with Eurasia, and in particular Central Asia. Furthermore, it helps India diversify its Eurasian connectivity along with INSTC, arranging for reorganization of freight traffic from the traditional sea route to land transcontinental routes.

- Eurasian Economic Union- India Trade Pact

Recently, India and the Eurasian Economic Union worked out details of Free Trade Agreement. The five member nations— Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan— jointly with India conducted a feasibility study “Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement”. The report highlighted lack of a formal trade and economic partnership, inadequate trade architecture and connectivity as chief obstacles— suggesting trade in goods, services and investment as potential solution. The technical meeting held in January 2018, served as a precursor for improved business interaction between India and EEU nations.

Notably, Modi on all his foreign visits has clearly outlined the importance of commerce, trade and connectivity in the future for India-Eurasia relations. He has energetically expanded economic cooperation, security architecture and political reach of the Indian diplomatic practices. In the 20th century India had adopted non-alignment rhetoric, reflected in limited trade and bilateral relations with Eurasian countries and the world in general; however in 21st century, especially with the change of guard in 2014, India has continuously expanded its Eurasian diplomatic relations. Given India’s newfound multi-alignment doctrine, it will most likely play a role of counterbalance in the Eurasian region (more particularly Central Asia), especially with regards to China’s expansionist policies.

- Pipeline Diplomacy

A stepping stone in this regards is then the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan and India (TAPI) pipeline or at the moment stalled Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline. Not only do they hold key to improved connectivity but also stage-manage the future role of India as the regional balancer with its enhanced economic and military cooperation. Definitely these pipelines will bolster India’s international image further, but one should not forget— India is a developing nation with one of the fastest growing economies in the world, which is plagued by energy resource scarcity. In this light then, in 2017, the Standing Committee on Petroleum and Natural Gas in the Indian Diet suggested that given the improved international conditions, following the lifting of sanctions against Iran, a business case for the revival of the IPI pipeline should be made.

- Stability in West Asia

Another significant contributor to India’s Connect Central Asia Policy is stability in Afghanistan. However, given that both Taliban and IS are competing for Afghan territory, the situation is set to get worse, with the constant infighting in Kabul’s ruling establishment, adding fuel to fire. While, India is progressing on the Chabahar Port in Iran, it is now required to strategize an effective regional approach which involves Iran and Central Asian countries, in addition to Russia. This will help India safeguard its interests in Eurasia, along with a close alignment to the US. Notably, in this context, Russia too is interested in creating one such inventory where it is able to bring Afghanistan, China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Central Asian countries and the US on the same table, albeit in a Moscow format.

If 20th century saw the Great Game over Eurasia unfold between Russia and Britain, (and later) the US; the 21st century Great Game is now finally unfolding in Eurasia, with multi-alignment approach projected by all nations; thereby testing India’s Eurasian strategy constantly.

Central Asia, and in larger part the Eurasian region, definitely is fundamental to the very development of India. With energy resources being the primary trade commodities, India is keen to connect with the region, stimulated by fast tracked infrastructure installation and policy implementations. India, as such does recognizes its position in the geopolitical arena, and is working towards proposing an alternative to China’s OBOR.

Moreover, China has increasingly been investing in Central Asian region and has actively participated in pipeline diplomacy in the region. In order to protect its sovereignty in the Indo-Pacific, India too needs to leverage its holistic Eurasian connect, and not just cultural rhetoric, by identifying other potential sectors for cooperation, be it economic, defense, energy or infrastructure. However, in doing so India needs to find common grounds with respect to each Central Asian nation, given their distinct political and cultural history; thereby bolstering inter-state relations to catalyze Eurasia- Connect Central Asia- Strategy, all the while mindful of its domestic needs.

Given the geo-political and geo-economic climate of 21st century, India, though in arrears, has now clearly grasped the importance of Eurasian heartland. India intends to now tap into the full potential of the region, which until now has functioned as the fulcrum for all the geopolitical transformations of historical significance within this “World Island” (Europe, Asia and Africa). In other words, Indian foreign policymakers have finally understood the essence of Mackinder’s theory— which he summarized in his 1919 classic “Democratic Ideals and Reality” as follows:

“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

Who rules the World-Island commands the world.”